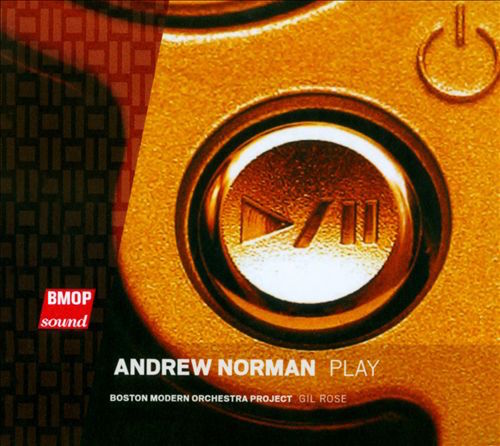

What is the worst thing that would happen if you publicly admitted to being in throbbing love with the oeuvre of Phil Collins or the decidedly non-artisanal bite of Evan Williams bourbon? The pasty guy at the record store counter may mutter, “Typical…”, but it would be freeing, right? Andrew Norman’s Play is no such “guilty” pleasure, but the score reads as though written by a composer unrestrained by any hint of self-consciousness. It is also one that is acutely aware that audiences trek in and shell out bills to see a show not to hear music, but to watch it performed.

“Level 2” of the three-movement opus is most emblematic of this, as it instructs the performers and conductor to physically “freeze” between gestures. Its efficacy lies in what is perhaps the most compelling element of this work, which is the unrelenting build of expectation. Norman’s triptych opens with maximum energy, and over the course of the work, recedes into the single pitches that close it. In this second episode, a trumpet outlines the triangular shape with a rhythmically receding C before the string sections begin tapping un-pitched 8th-notes, whipping their fingers over the strings like a classical guitarist with dodgy left-hand technique.

Backing up for a moment, “Level 1,” with its maximalist counterpoint and unrelenting scales has just inserted itself as the new, best excerpt with which to introduce children to classical music. String glissandi and brass outbursts play like the uninhibited predilections of toddlers, and for adults, reignites a sense of whimsy and wonder.

The Boston Modern Orchestra Project, led by conductor Gil Rose, is as essential to the success of this album as the score itself and the ensemble’s aesthetic buy-in is palpable. This is most evident in the aleatoric segments, in which the players draw seamless lines between non-aleatoric material to a Berio-sequenza-like effect. Riding the high of the previous two movements, the intimacy of “Level 3” is introduced like a epiphany, unafraid to embrace the universal appeal of a dependable beat and cathartic harmonic progressions like the best of cinematic end credits. Ebullient, soaring brass and woodwind lines hover over exuberant string surges as the piece unwinds.

There are no unfamiliar instrument manipulations relied on in Play, which makes the number all the more intriguing in its minty freshness. While the inclusion of one of the piece’s earlier iterations, Try, offers listeners an intriguing insight into the development process of such a large-scale undertaking, even a first pass at Play gives the impression that something rare, something uninhibited, is happening here.

- Doyle Armbrust