Do you remember the time you felt most like a stranger…like a human distinctly out of place?

For me, this moment arrived during the week of New Year’s in 1999, when I awoke in an unfamiliar bed in Bethlehem to the adhan, the call to prayer, jet-lagged to all hell and bewildered by the proximity of a bewitching, undulating voice. The escape from my stupor was delicious, and the reemerging realization that I had joined a local handbell choir back in Chicago just to piggyback on their tour here didn’t diminish my wonderment. Later, out on the dusty street, there’s no question that I was the one seriously out of his element.

Sound was the transportive expedient in that moment.

Edgard Varèse did not have to join a handbell choir to make his way to America, if we are to believe the musicologists. Not to be outdone by the near ubiquitous —amongst successful people, anyway—immigration story of “arriving with just twenty bucks in my pocket….” Varèse went next-level for the benefit of his future biographers by moving to the US only after all his compositions were destroyed in a Berlin warehouse inferno.

Now that’s an origin story.

Even with Amériques, the first piece he would pen in his adopted country, the real fascination is found not in Varèse’s expatriation, but rather in his sonic wanderlust. He believed classical music desperately needed a new palette of sounds beyond the orchestra—and that Schoenberg and the rest cared too much about preserving elements of tradition in the midst of musical progress.

Yes, he sounds like a suspiciously old undergraduate composition student insisting he’s, “unlocked the future, man,” just before scooting off to his late shift at Best Buy…but no, Edgard is the real deal and was simply born a bit too early in relation to the introduction of the synthesizer.

Amériques pre-dates these electronic advancements, though, finding its unique voice through the inclusion of a very prominent siren, a preponderance of complex rhythmic structures, and hey, because this is the land of opportunity, why not a whole mess of percussionists? While this piece is meticulously constructed—with delightful recurrences of musical morsels and a clearly defined scope of available sounds—the first time one shares this nimble little number at book club or on a road trip, that aforementioned siren is going to raise an eyebrow or inspire a chuckle. These are appropriate responses. No one will ever convince me that Amériques is entirely self-serious, or that its conclusion is any more elevated than a Monty Python sketch. It captures the ebullience and the absurdity of, say, the fact that a life’s work can evaporate in an instant, forcing one to uproot to New York City, and eventually be stalked by over-eager nerds like Frank Zappa and Charlie Parker.

Speaking of unexpected instruments, how genius is George Gershwin for including actual car horns in his An American in Paris? In the realm of classical music it’s not uncommon to obsess over, for instance, what a theorbo played by a dyspeptic swineherd would have actually sounded like in the era of Monteverdi, or whatever. To each their own, but in the case of this new Gershwin Initiative edition from which the CSO is performing, the piece’s most instantly recognizable feature—the taxi horns—now boast new pitches, and it really does re-tune the listener’s experience, of Gershwin’s experience of, the sounds caroming around the frenetic Parisian motorways.

As with Varèse, the real “stranger in a strange land” storyline here is not so much about Gershwin experiencing Paris as the Tin Pan Alley Gershwin struggling to find legitimacy in the so-called “high art” of classical music. Poor George was so self-conscious about criticisms of his orchestration abilities that he begged Maurice Ravel to become his teacher. Maurice, already a fan, told him his tutelage would just get in the way…and if Maurice-freaking-Ravel tells you he has nothing to teach you, um, perhaps you’re on to something.

So, Gershwin is giving us a sonic impression of Paris, and yet really what he’s doing is perfecting his own, uniquely American approach to orchestral writing. It’s almost as if he’s hoodwinking conservative classical audiences into his world by distracting them with the perceived exoticism of Europe, as in,”Of course this sounds unusual, it’s France!” Oh wait...did you just catch that a little over 14 minutes in? That’s the opening of the Molto vivace movement from Beethoven’s 9th, all stacked up on top of itself. Take it easy, George, you don’t need to kiss the ring for this to work.

As Louis Langrée and the CSO beckon you toward a more elegant An American in Paris than you’ve likely heard to-date—one with rounder angles but finer points—I’d like to encourage you to tune your ears to George: the jazz-classical alchemist struggling with a serious case of concert-hall imposter syndrome rather than Gershwin: United Airlines jingle-writer and season-subscriber “safe play.”

You know who else assured Gershwin that he didn’t need her help? Nadia Boulanger, god bless her. She’s also more or less responsible for Astor Piazzolla’s tangos infiltrating classical concert halls. And if this weren’t enough for you to fall in love with her, she housed her friend Igor Stravinsky during the bleakest year of his life: the one in which he lost his mother, wife and daughter.

In this darkest hour, one can only imagine what a stranger Stravinsky felt like in his own skin. Add to this the composer’s own somewhat itinerant life-residing in Russia, Switzerland, and France—and you have a recipe for an unpredictable existence.

Perhaps it’s interesting—or maybe it’s just irresponsible projection—to note that it’s curious that Stravinsky arrives in the U.S. at the advent of WWII with a half-written symphony under his arm, centered around that warmest of all tonal blankets: C major. This trailblazer, who cleaved his musical path using antique tools (so to speak), turns back not only to the realm of the symphony, but to classical music’s home base key. At least from the outside looking in, this smells like a creative desiring sure footing. Something familiar and grounded, though of course manipulated in astounding ways that would inspire generations of composers in his wake.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Symphony in C is also a travelogue of sorts, but of a different flavor than either An American in Paris or Amériques. If the Gershwin is a full-blown tone poem, and the Varèse is only abstractly connected to a first impression of the U.S., Stravinsky’s masterful symphony finds its geographic inspirations almost unintentionally. If I may be so bold, flip on the first movement and then after a few minutes, skip forward to the third. You experienced a bit of stylistic whiplash here, right? The composer claimed that he could not have effectively written the first two movements in America (they were drafted in France), and that the third and fourth could have only been invented amongst the purple mountain majesties (composed in Massachusetts and California, respectively). Or put another way, the classical nuance of movements one and two benefitted from the noble traditions of Europe, while the audacious rhythms and counterpoint of movements three and four thrived in the “anything can happen” atmosphere in the U.S. of A.

For those of you still reading, I tip my hat, and I reward you with a word of caution. Stravinsky is a gateway drug into the Wild West of contemporary music. A young person takes one drag on an Igor score, and the next thing you know, they’re on a Pierre Boulez binge, a Kaija Saariaho spree, or a Tyshawn Sorey splurge. You’ve been warned.

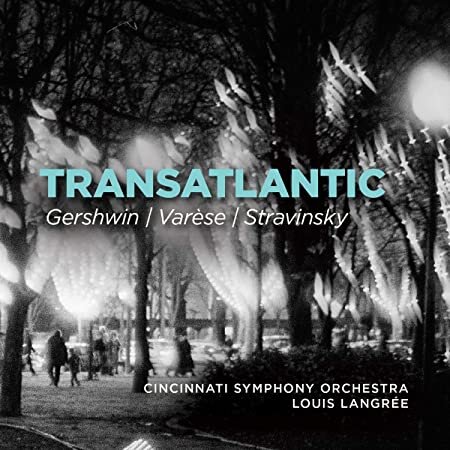

These three magnificent works are about “otherness,” both on their surface and in their deepest layers. They are about building bridges, and the ways in which creativity is magnified when borders—both tangible and aesthetic—are enthusiastically breached. But it is important to mention that you, the listener, can also choose to engage with this album on a purely sonic level. These are thoughtful, exhaustively polished, and indisputably eloquent performances by artists eager for you to share in their belief in this music—one which borders on fanaticism.

Welcome, stranger. You’re in for one memorable tour.

– Doyle Armbrust